It’s good to talk

by Executive Headteacher, Anthony David

There should be little surprise when study after study shows that getting children talking (oracy skills) can dramatically improve learning. The Education Endowment Fund (EEF) cites oracy strategies as the second most impactful strategy to improve children’s outcomes, with an estimated impact of +6 months for every academic year. Yet, strategic oracy opportunities remain stubbornly a distant third place to reading and writing.

So, why is this the case and how can you provide meaningful ways to get children talking purposefully?

What do we mean by oracy skills?

For those who have been teaching for a while, this is what used to be referred to as speaking and listening. Any intervention that provides opportunities for purposeful discussion is an oral strategy. Within schools this can come in the form of school or class council meetings, lesson specific discussions (within identified pupil conversation, such as paired work with a science activity), reading aloud, debates or strategic table talk. With the growing validation of pupil’s voices (championed, it would be fair to say, by OFSTED) schools are creating more opportunities to get children talking purposefully. Oral language opportunities may take the form of the following:

- Subject specific enriched language

- Intentional curriculum discussions

- Reading aloud within an ability range and corresponding questioning

- Listening opportunities to extend language capacity within context (e.g. in assemblies or within a whole class story)

Children who are confident speakers typically develop better independent skills (metacognition) and work more effectively in a group or team; they have stronger collaborative skills. Only metacognition scores higher than oral skills in the EEF’s teaching and learning toolkit. Given that one is reliant on the other, this reinforces the importance of being confident speakers. Confidence comes when children understand the context they are speaking in. It is, therefore, important to match the context to the vocabulary; this is how children make meaningful and deep links with the curriculum (what some school leaders refer to as ‘sticky learning’).

How do we create confident speakers?

At Picture News we say there are three types of communicators:

- Speakers

- Listeners

- Magpies

The challenge is giving children licence to move between all three forms of communication. There will certainly be times when a child feels full of confidence to be the speaker and others may need support from being listeners. What is less well defined is the case for the magpie. Children are experts and finding out from others what they need in order to improve; their capacity to glean from others is highly refined. However, this only happens when children can define a need to magpie. Professor Sugatra Metra set up this ‘need’ in the late 1990’s when he first trailed his famous ‘hole in the wall’ project. The need was established by giving a group of children a computer and not offering any advice in how to set it up and get it working. Within a very short space of time the children were able to get the information they needed to action something they wanted, in this case a working computer. It was a defined task where a clear need to share information was established.

Creating this tension of task versus the need to communicate is what drives learning; it naturally creates a ‘magpie’ environment. The challenge is balance; too many tasks or too many new words can erode as much as grow confidence. For our most vulnerable learners, this balance requires constant fine tuning and when new ‘talk’ opportunities are provided they need to be presented within a safe context that fosters involvement. Interestingly, the new pupil premium report framework has oracy as the first strategy to improve learning outcomes. The exemplar framework states:

Oral language interventions can have a positive impact on pupils’ language skills. Approaches that focus on speaking, listening and a combination of the two show positive impacts on attainment.

Given the impact that the EEF have found, this emphasis on speaking and listening is probably not surprising.

If it is so important, why does speaking and listening not have a higher profile?

The simple answer is that it is not assessed in schools in the same way as reading and writing. There is no SAT for this aspect of English and it is, arguably, difficult to make a judgement. If a school was assessing a child’s capacity to speak another language, such as French, this would never be the case. Speaking and listening would be considered as important and reading and writing skills. That said, companies such as the English Speaking Board and Noisy Classroom have been assessing and championing children’s speaking and listening skills for years so it could be suggested that training (in the same way that we train to moderate writing) is the need. Emma Hardy, Labour MP and shadow minister for Further Education, has led a cross party group to champion speaking within the curriculum, most recently as part of the national catch-up programme following the pandemic. There is growing political pressure from both main parties to make speaking and listening a core aspect of school learning.

How can Picture News provide support?

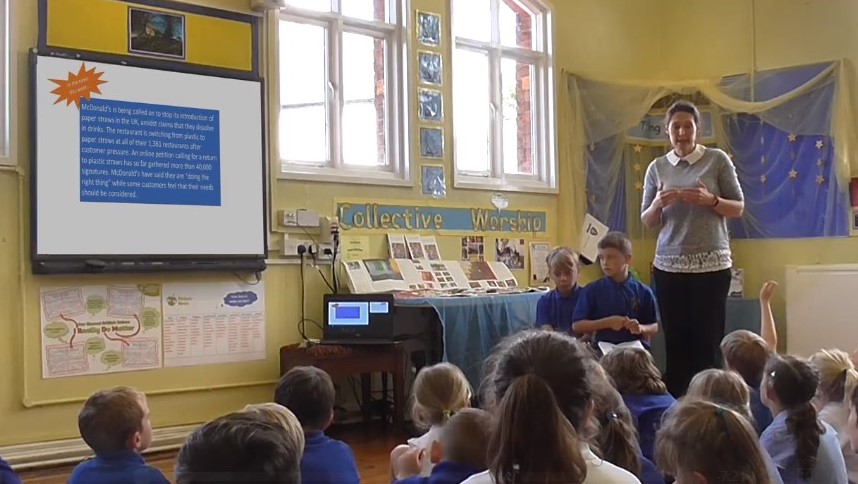

Our focus has always been on getting children talking purposefully about the news. Our starting point was to provide an image as a stimulus for discussion and to introduce children to new vocabulary. Over the last few years we have enhanced this original resource by looking at how we can make connections with British Values, children’s rights and, more recently, in our collective worship resources. They say a picture paints a thousand words, and it is that context that we use our stimulus photographs to provide contextual opportunities for children to think and talk about current affairs. By doing this they are able to, within a controlled context, exercise new vocabulary and thoughts. It is a safe place to challenge or make personal views.

What we understand is the importance of introducing children to new vocabulary and providing meaningful ways to use it. This is our drive and the focus for new resources as we develop them. Whilst we appreciate we are only part of the picture, our goal will remain constant; to provide real-world examples that give children a voice.